Teaching Approach

The fundamental goal of teaching composition for me is to assist and enable a student to locate and develop his/her unique compositional voice. Composing and even mere guidance in the craft of composition today presents a particular challenge, in that a young composer’s search for a personal sound takes place amidst an unprecedented plurality and accessibility of musics. Navigating this vast terrain of offerings without getting lost, overwhelmed, or discouraged requires from a composer first and foremost confidence in and knowledge of oneself and one’s own unique interests, passions, and abilities.

A “pedagogical” response to dealing with the vastness of our musical cosmos might be for the instructor to create delineations and demarcations in an attempt to present the student with an ostensibly clear orientation, within which he or she can (or «should») develop. This approach seems to me only partially adequate, given the course of how concert music composition has evolved in the 20th century: composers such as Schoenberg, Ives, Varèse, Cage, R. Murray Schafer, or Helmut Lachenmann have profoundly shocked historically established definitions of what «composition» can be. To transmit knowledge about these composers (and of course many others), the conditions they were working under, and the questions they have raised, to me seems very helpful to lay out a foundation to sharpening an awareness for what the student of composition is doing.

To this end, it is important to cultivate true curiosity, and to open the ears and the mind for all forms of "organized sound". This will certainly encompass excursions into related areas of sonic practice, such as jazz and free improvisation, field recording, electronic music, sound design, film music, and sound installation - in fact, all areas of geophony, biophony, and anthrophony (to use Berne Krause’s terms). As composers, we need to hear and know as much as at all possible, in order to find out what kind of personal «resonator» we are.

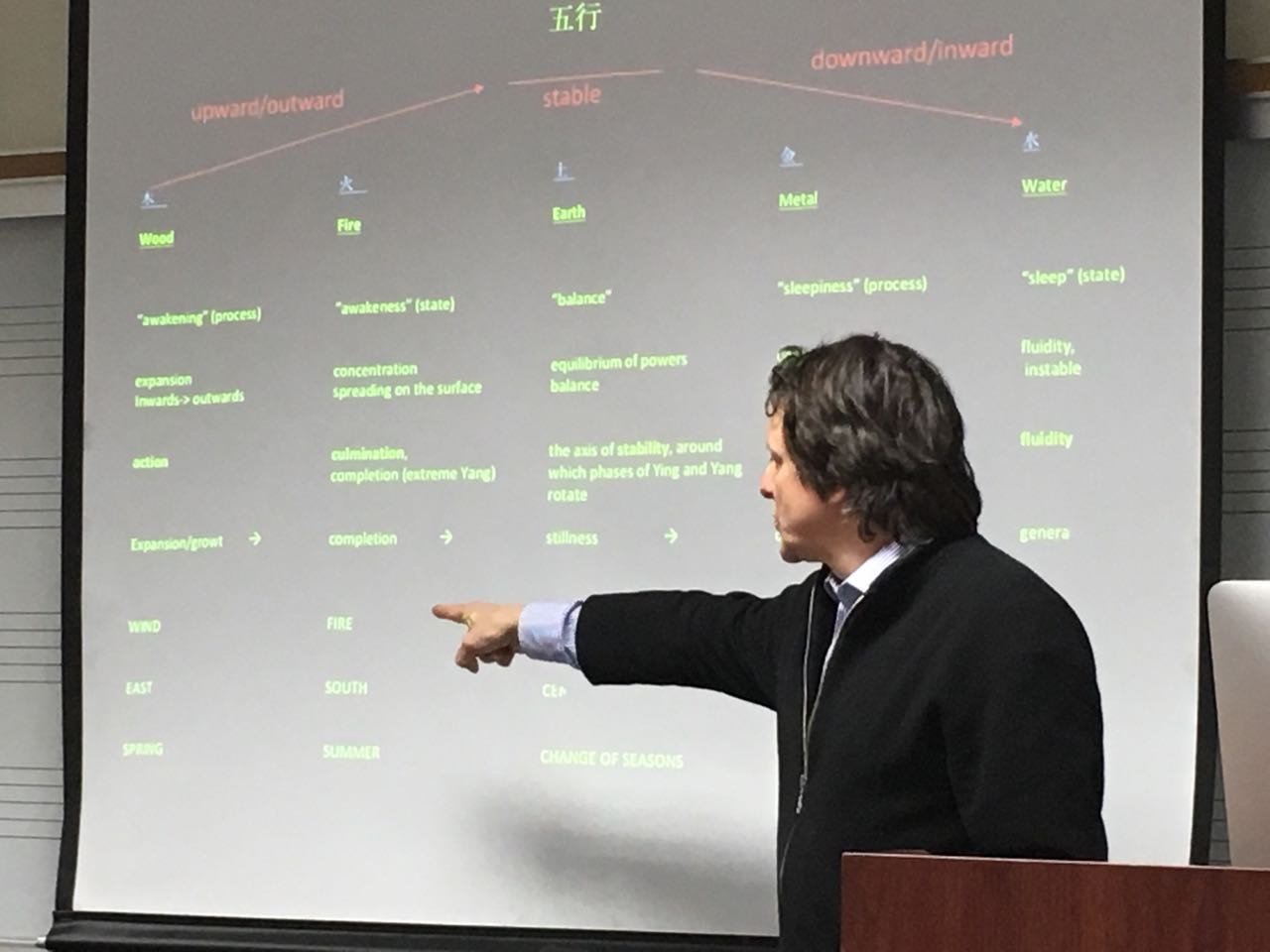

Of defining importance are musics from non-Western cultures (in particular African, Indian and East Asian) as well as electronic and computer music. I insist on keeping my approach free of dogmatic assertions and stylistic/aesthetic value judgements, and instead try to primarily focus on the activity of descriptive and analytical listening: when presenting a new piece, I frequently play a recording of the piece to the students, first without the score (or other visual representation). Subsequently, we try to reconstruct the piece from memory: which instruments/voices have been heard? Which musical language is at work? What rhythmic, melodic, harmonic, timbral characteristics can be discerned? How can the form of the piece be described? This discussion is then followed by the acquisition of knowledge: we hear the piece again, this time with the score, matching up and comparing what we remembered with what we can now see. Background information is provided at this point. I have applied this sequence in my seminars in Berlin, Stuttgart, Hannover, Rochester and Düsseldorf with productive, often completely unpredictable, but always stimulating results.

Pierre Schaeffer’s concept of écoute réduite (reduced listening) plays a crucial role in this approach: an analytical form of ear training arises from a quasi-phenomenological «observation» of the sound itself (- rather than judging it immediately, describe it first), in conjunction with the listener’s own experiential prerequisites.

I believe that this exercise in listening and remembering aids in the development of an ability to imagine sonic scenarios and environments, as well as a facility in analyzing other composers’ works. Students should be challenged to unfold and articulate their individual listening perspectives, while communal aspects of learning from peers by comparison and discussion are of equally vital importance.

Contact here.